Keep Pydantic out of your Domain Layer

You’re probably reading this because you’re using Pydantic yourself. Maybe you’re building a FastAPI application and hit a point where it started getting too big to manage, and you realized you need better separation of concerns. Perhaps you’ve started adopting a clean architecture or onion architecture kind of layering to keep business logic separate from application logic, aiming for better maintainability and testability. But Pydantic is starting to creep into every layer, even your domain, and it starts to itch. You know you don’t want that, but you’re not quite sure how to fix it. If that’s you, then you’re standing at the same crossroads I once did. Keep reading :)

You’ve probably been spoiled by the amazing features Pydantic has to offer. It’s incredibly convenient to spin up an entire hierarchy of nested objects by simply passing in a multilayered dictionary. Which makes Pydantic fantastic for data validation and that’s probably the main reason you should use it for.

Pfff, who even cares? Yeah yeah, with great power comes great responsibility… But why shouldn’t I just use Pydantic everywhere? It’s so convenient, what’s the harm?

And like almost everything in software engineering… it depends. If you’re building a simple CRUD app, it might feel like overkill to write a bunch of extra boilerplate just to keep Pydantic out of everything except the edges of your application, like the presentation and infrastructure layers. But as your application grows, this tight coupling can turn into a liability. That’s when concerns like loose coupling and separation of responsibilities start to matter more. The less your core logic depends on specific tools or libraries, the easier it becomes to maintain, test, or even replace parts of your system without causing everything to break.

But how to translate Pydantic BaseModels to Plain Old Python Objects?

There are a few ways to approach this, and one of them is using Dacite. I’ll start with a quick and simple example using that library alongside the most obvious alternative. After that, I’ll demonstrate how Dacite can be used in a more structured, layered setup, with a clear separation of concerns between the different parts of your application.

Dacite

What mainly makes it difficult to convert a Pydantic BaseModel to plain Python dataclasses is that, quite obviously, it takes a lot of manual work to re-initialize the nested structures, especially if you already have a fairly deep object hierarchy. Dacite is a tool that takes care of much of this heavy lifting for you and was specifically designed with this purpose in mind: initializing nested dataclasses from a dictionary. So here’s a small and overly simplified example.

from pydantic import BaseModelfrom dataclasses import dataclassfrom dacite import from_dict

class AddressModel(BaseModel): street: str city: str

class UserModel(BaseModel): name: str address: AddressModel

@dataclassclass Address: street: str city: str

@dataclassclass User: name: str address: Address

user_model = UserModel(name="Alice", address={"street": "Main St", "city": "Wonderland"})user = from_dict(data_class=User, data=user_model.model_dump())

print(user)# User(name='Alice', address=Address(street='Main St', city='Wonderland'))You might be asking yourself: Do I really need yet another third-party library? In this case, the answer is no, you could absolutely do this manually. And in practice, you might not need it either. Especially if you’re working with aggregates and entities in a DDD-style architecture, it’s considered best practice to keep those hierarchies relatively simple. If the tree of an aggregate becomes too large or deeply nested, that’s generally a code smell.

So, do you really need it? I know many developers prefer to avoid third-party libraries whenever possible, and for good reason. Personally, I like to keep my codebase as readable and transferable as possible. And if Dacite helps me achieve that, I’m happy to consider using it.

So in this case, you could have done it manually… And you can probably already imagine what that would look like, but for the sake of completeness:

...user_model = UserModel(name="Alice", address={"street": "Main St", "city": "Wonderland"})user_model_dict = user_model.model_dump()user = User( name=user_model_dict.get("name"), address=Address( street=user_model_dict.get("address", {}).get("street"), city=user_model_dict.get("address", {}).get("city") ))print(user)# User(name='Alice', address=Address(street='Main St', city='Wonderland'))You can probably imagine what that would look like with more fields. But maybe it can also serve as a good incentive to keep your structures as simple as possible. In the next example, I’ll continue using Dacite anyway.

A Better Structured Approach

The previous example was nice to quickly get a sense of the functionality of Dacite and the obvious alternative for translating Pydantic Basemodels into pure old Python dataclasses. Now let’s move on to a slightly more practical and better-structured approach, where the dataclasses are actually part of the domain layer as entities, and the BaseModels belong to the application or infrastructure layer.

To keep things clean, maintainable, and well-structured, I prefer introducing a small set of supporting objects that act as a bridge between the application and the domain.

Small note before we continue: While I did mention BaseModels, in this “structured approach” I’m using plain dictionaries instead of actual BaseModel instances, just to keep the example focused on domain structure and layering with Dacite handling the conversion back and forth between plain dicts and domain entities. In a real FastAPI application, the data would typically come from a Pydantic model and be converted to a dict using .model_dump() before passing it to the mapper. You could also let the mapper handle the .model_dump() and pass the BaseModel directly to it, but I chose not to.

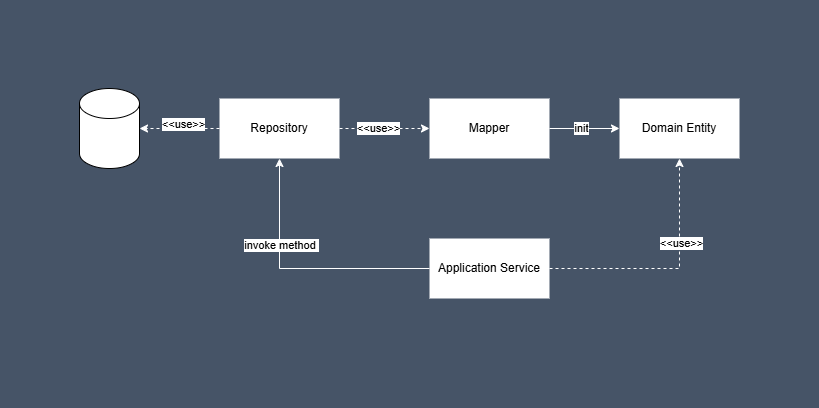

The diagram might speak for itself, but just in case it doesn’t, here’s a quick breakdown:

- The application service interacts with a repository1, which could be backed by a database, file storage, or another data source.

- The application service interacts with the repository class by calling any of its basic methods such as

get,get_all,save, ordelete. - The repository is responsible for storing and retrieving data. It also translates between the storage format (typically

JSON,YAML, or plaindicts) and domain entities using a mapper. - When calling a retrieval method (like

get), the repository returns a fully-initialized domain entity to the application layer. - The application layer can then:

- Invoke domain logic directly on the entity.

- Pass the entity back to the repository when it needs to be saved via the

savemethod.

I won’t go too deep into the responsibilities of a repository here, as that’s not the main focus of this article. However, I do want to emphasize that a repository should stay simple and always interact with a single aggregate.

How would this look in code?

.├── application_service.py├── repository.py├── mappers/│ ├── mapper.py│ └── recipe_mapper.py└── domain/ ├── recipe.py └── shared/ └── entity.pyLet’s start by defining some base classes that other entities will inherit from. Besides making it clearer which entity is an aggregate root and which is a regular entity, it also allows us to define common equality and hashing rules that can be used by all child classes2.

from dataclasses import dataclassfrom typing import Any

@dataclassclass Entity: id: int

def __eq__(self, other: Any) -> bool: if isinstance(other, type(self)): return self.id == other.id return False

def __hash__(self): return hash(self.id)

@dataclassclass AggregateRoot(Entity): """ An entry point of aggregate. """ passNow that we’ve defined the base classes we’ll be inheriting from, we can define the actual entities for our example.

from __future__ import annotationsfrom dataclasses import dataclass, fieldfrom domain.shared.entity import AggregateRoot, Entity

@dataclassclass Recipe(AggregateRoot): title: str instructions: str ingredients: list[Ingredient] = field(default_factory=list)

def add_ingredient(self, ingredient: Ingredient) -> None: self.ingredients.append(ingredient)

def remove_ingredient_by_name(self, name: str) -> None: self.ingredients = [i for i in self.ingredients if i.name != name]

@dataclassclass Ingredient(Entity): name: str quantity: strI’ve added some basic functionality so you get a more complete picture of where the responsibilities lie. While it might be tempting to modify the ingredients attribute directly, you’ll want to delegate that responsibility to the aggregate root instead, by applying the changes through methods. This helps keep the code more adaptable and maintainable.

Now that the domain is ready, we can move on to the mappers. We’ll start with an abstract base class (ABC), allowing us to program against abstractions instead of concrete implementations. This makes it easier and safer to add new mappers later on.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethodfrom typing import Any, Generic, TypeVarfrom domain.shared.entity import Entity

MapperEntity = TypeVar("MapperEntity", bound=Entity)MapperModel = TypeVar("MapperModel", bound=Any)

class AbstractDataMapper(Generic[MapperEntity, MapperModel], ABC): entity_class: type[MapperEntity] model_class: type[MapperModel]

@abstractmethod def model_to_entity(self, instance: MapperModel) -> MapperEntity: raise NotImplementedError()

@abstractmethod def entity_to_model(self, entity: MapperEntity) -> MapperModel: raise NotImplementedError()For each repository and aggregate, we create a separate mapper that is responsible for translating the data to and from the aggregate.

from domain.recipe import Recipefrom mappers.mapper import AbstractDataMapperfrom dataclasses import asdictfrom dacite import from_dict

class RecipeDataMapper(AbstractDataMapper[Recipe, dict]): def __init__(self, entity = Recipe, model = dict): self.entity_class = entity self.model_class = model

def model_to_entity(self, instance: dict) -> Recipe: return from_dict(data_class=self.entity_class, data=instance)

def entity_to_model(self, entity: Recipe) -> dict: data = asdict(entity) return self.model_class(**data)The repository will use the mapper to translate the retrieved data into the appropriate aggregate and return it to the caller. It can also translate an entity back into a model (for example, a dict) and persist it to the database.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethodfrom domain.recipe import Recipefrom mappers.recipe_mapper import RecipeDataMapperimport yaml

class AbstractRepository(ABC):

@abstractmethod def get(self, id) -> Recipe | None: pass

@abstractmethod def save(self, recipe: Recipe) -> None: pass

class FileRepository(AbstractRepository): def __init__(self): self.mapper = RecipeDataMapper()

def get(self, id) -> Recipe | None: with open(f"{id}.yaml", "r") as file: data = yaml.safe_load(file) return self.mapper.model_to_entity(data)

def save(self, recipe) -> None: data = self.mapper.entity_to_model(recipe) with open(f"{recipe.id}.yaml", "w") as file: yaml.safe_dump(data, file, sort_keys=False)Finally, we arrive at the application layer, which essentially puts everything to work. It acts as the orchestrator and is responsible for calling the appropriate layers and invoking the right methods.

from repository import AbstractRepository, FileRepositoryfrom domain.recipe import Ingredient

class ApplicationService: def __init__( self, repository: AbstractRepository ): self.repository = repository

def add_ingredient_to_recipe(self, id, ingredient): recipe = self.repository.get(id) recipe.add_ingredient(ingredient) self.repository.save(recipe)

application_service = ApplicationService(FileRepository())application_service.add_ingredient_to_recipe( id=5, ingredient=Ingredient(id=3, name="extra ingredient", quantity="100g"))So… Where Should Pydantic Live?

Pydantic is great, just not everywhere. Ideally, it should live in the outer layers of your application: for example in the infrastructure layer when interacting with external APIs or databases, and in the presentation layer for request/response validation in FastAPI. Keep it out of the domain core. Not because it’s bad, but because your domain should be pure and independent.

That’s all folks

If you enjoyed this article, feel free to share it or tag me on LinkedIn (or anywhere else). Got questions or feedback? Don’t hesitate to reach out. You can also email me at erikvandeven100@gmail.com.

Footnotes

-

I might write a separate blog post to dive deeper into repositories, but in the meantime, I highly recommend checking out Cosmic Python, it has an excellent chapter on this topic. It’s an amazing book and definitely worth a read. ↩

-

The code for the

EntityandAggregateRootclasses was originally written by Dong-hyeon Shin. ↩